Are Scotland’s teachers prepared, confidence, competent, and/or ready to teach?

The Measuring Quality in Initial Teacher Education (MQuITE) project is trying to find ways to measure quality which reflect nuance and distinctness suitable for our context in Scotland, while also building in international comparisons wherever possible. This makes the phrasing of our questions all the more important – we want something meaningful locally, but which resonates internationally. English is rich with near-synonyms, so while we can compare responses from one survey asking if teachers feel competent with another survey asking if they feel confident, it’s not ideal. Indeed, even if respondents are answering an identical question, we might want to seek some reassurance that they understand it in the same way. In a study such as MQuITE, where we put some of the same questions to new teachers, teacher educators, and school mentors, we would also want to check that these different groups had the same understanding of key words.

The OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) gives us a good place to start since it sets out to conduct cross-country analysis for more than 30 countries. The teacher survey (question 13) asks “In your teaching, to what extent do you feel prepared for…” and then giving five response options for content, pedagogy, and classroom practice in the subjects which a teacher is required to teach in their current role. There is also a question about whether feedback improved the teacher’s confidence (question 30) and if teachers are confident in their judgements of students (question 47). The French version of the survey uses préparé (question 13) Votre confiance en vous en tant qu’enseignant(e) (question 30) and Je me fie à mon jugement à propos des élèves (question 47). Even with the similar etymologies, some small differences appear – question 13 is an unproblematic translation, but question 30 now has a feel of being more about confidence in oneself as a teacher rather than just confidence as a teacher, and question 47 is more about trusting one’s judgements rather than being confident per se – again, similar, but not quite the same since confidence relies on evidence but trust does not. We can have some confidence/trust in OECD to have extensively piloted and analysed different phrasing, but these small differences in what are linguistically close languages show how international comparisons could be problematic. Unfortunately, OECD only shares its English and French versions, but it has shared some of its statistical techniques of invariance analysis which make for a reassuring read.

Aside from these small nuances, we might wonder why preparedness is used for specific aspects of teaching and confidence/trust for judgements made as a teacher and general feelings about one’s own performance. Does preparedness not work as well in a general sense, or does confidence not work as well in a specific sense? We can also add other phrases to the mix – such as readiness or competence, or even effectiveness (although this seems to be imply more quantitative measurement, it seems to have resonated in the Studying the Effectiveness of Teacher Education project in Australia). With such phrases comes more complexity, take this tweet from Phil Race as an example:

If we do not know how a teacher understands a key word in a survey question, then we will struggle to understand their response. In a qualitative interview, we might luxuriate in such nuances. In a survey, it’s tricky. At the same time, we might really want to get an impression of more complex concepts – if teachers reported feeling competent but not confident, this would be something we’d want to look into more. For instance, a PhD looking at teachers’ confidence teaching mathematics suggested that teachers lacking confidence may compensate by being highly prepared: they would stick close to the textbooks and lesson plans, seeing them as “a lifeline” for them as teachers rather than “in support of learning” for their pupils (Marino, 2003, p.35).

In the MQuITE survey for 2018 graduating teachers, we stuck with prepared as our subject-specific question (and we’ll give a much more detailed breakdown of preparedness ratings for different curriculum areas in another post). This matches with its use in TALIS, and in the US Beginning Teacher Longitudinal Survey (question 37).

In MQuITE, this meant we asked:

- In general terms, how prepared do you feel to enter the teaching profession?

- As a beginning teacher, please tell us how prepared you feel to teach the following… (followed by a list of curriculum areas)

- Please rate how competent you feel as a beginning teacher

- Please rate how confident you feel as a beginning teacher

Notice the use of bold in the questions to try draw attention to the different focus from the previous questions on preparedness, and how the question was framed in terms of entering the profession or being a beginning teacher. We also asked school and university staff “How well prepared do you believe ITE graduates are to take up posts as beginning teachers?”, but did not ask about competence or confidence here.

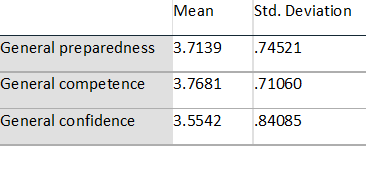

Starting with the graduating teachers, we can see that ratings for competence, confidence, and preparedness are all at similar levels:

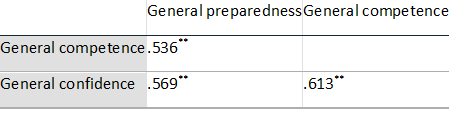

Feeling apprehensive at the start of a new career seems reasonable, although the larger standard deviation for confidence also suggests that this is the most varied of the three measures and so some students may be less confident than others even if they feel similarly prepared and competent. It’s also interesting to see the Spearman correlation here:

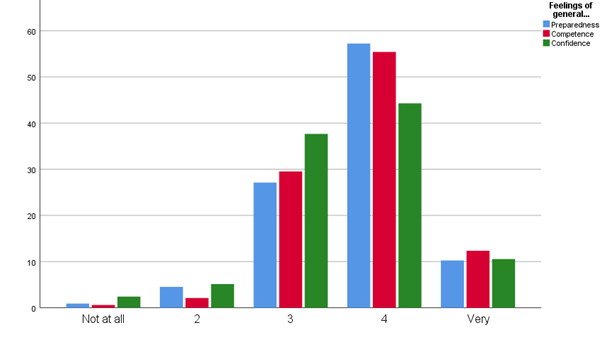

which suggests that these are not simply synonyms to these teachers. It’s quite difficult to show relationships on 3 variables, but if we look at a simple chart we can see there are similar numbers feeling very prepared, competent, and confident, fewer graduates are reporting 4/5 confidence, and reasonable minorities are reporting much lower confidence.

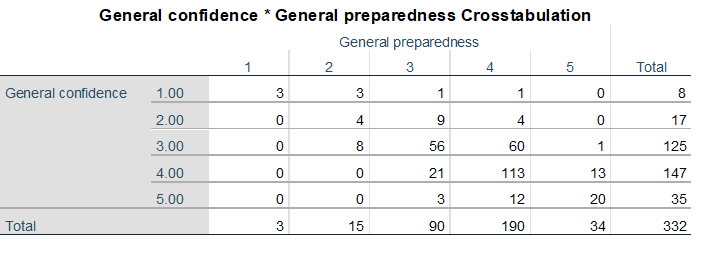

If we just focus on two variables, we can plot them against each other as in this table:

Reading diagonally shows that there are significant numbers of teachers giving the same rating for both variables, but there are also plenty of differences too, including many more than one point away.

We can also draw comparisons across the other MQuITE surveys for preparedness:

- 2018 graduating teachers: 3.68

- University staff: 3.94

- School staff: 3.02

Here we see that school staff, which in this case includes teacher mentors, headteachers, and some senior school leaders, give a positive rating for how prepared they think new graduates are, but only just. University-based teacher educators give a much higher rating – higher, in fact, than the new teachers give themselves. MQuITE is going to look at ways to understand this in focus groups, but one idea for now could be that preparedness has quite different meanings for these three groups. It will also be very interesting to see how these new teachers rate their preparedness as they progress through their programme, and how they later reflect on how prepared they were at the start of their teaching careers.

References

Marino, P. (2003). The National Numeracy Strategy and primary teacher confidence as perceived by teachers. PhD thesis. Bath: University of Bath.

This blog post was written by Dr Mark Carver (@themarkcarver), research assistant on the project.