Are Scotland’s teachers sufficiently prepared to teach numeracy?

The recent ‘Is there a better way to teach our teachers?’ article in the Herald (November 18th) returns to the topic hotly debated by the Scottish Parliament Education and Skills Committee where five graduating students were questioned about their perceptions of their own Initial Teacher Education. The students were forthright, with one primary education student claiming “I do not believe that everyone who graduated this year has sufficient skills in numeracy to be able to teach it to 11-year-olds at a reasonable standard.” This is a bold statement to make about a whole year group, based on one’s personal experiences. Indeed, whilst it might be argued that such statements are, at the very least, unhelpful, this, and other offerings, created something of a furore. In response, we here offer some caveats for why such missives might not be the dilemma they immediately seem.

First, graduating from initial teacher education does not make one the finished product. The first year of teaching, the “Probationary Year”, is regarded as the early phase of professional learning, with teachers subsequently expected to be lifelong learners. With so many different combinations of subject and level, it is impossible for any teacher to be fully prepared for every eventuality. This is why teachers are assigned to specific classes rather than simply at random – not every teacher will teach numeracy to 11-year-olds. Schools play to strengths, and they support lifelong learning for their teachers.

Second, measuring a ‘reasonable standard’ is more difficult than it seems. Teachers who are academically “good at” a subject are not necessarily skilled at teaching that subject. Similarly, just because someone is less proficient at, say, maths, is no reason why they might not be particularly skilled at teaching this to 11-year-olds. Even if we just take the simple “nobody knows their times tables by heart anymore” complaint we can see that there is an assessment problem. We might take the approach of England and Wales and give a simple numeracy test to all students before they are allowed onto the course. We might even take the approach of many US states of having multiple-choice exams before a teaching certificate is awarded. In each case, whilst this might make us feel better about the level of maths a graduate might have, it reduces “skilled in numeracy” to something much more like “good at maths”. This is no guarantee of pedagogic success. Since all initial teacher education in Scotland is university-based, giving so much power to multiple choice tests implies a lack of trust in the effectiveness of ongoing assessment throughout a degree programme. There might be valid uses of such ‘quick and dirty’ tests, but certainly, these universities have high entry requirements. As well as advanced and higher qualifications, IB or A-levels, there are minimum standards for maths and English set by the GTCS. If a student can be successful at school and college, passing maths exams sufficient for entry to some of the best universities in the world, then graduate from that university whilst also satisfying their peers in the teaching profession that they have met national professional standards, then perhaps we do not need to shout “What’s 7 times 9?” at any passing teacher.

Third, we might also suggest that a self-selecting group of five students is hardly representative of the almost 4000 students graduating as teachers every year in Scotland. Indeed, currently, we do not really know how representative their views might be since we have not asked these types of questions at scale. The quality of Scotland’s teacher education is currently mostly an inference based on GTCS accreditation of the 38 ITE programmes, inspections of the schools and universities, the ongoing assessment and professional development of teachers in schools, and the standards achieved by learners through measures such as a value-added score. If a teacher really were unprepared, we would hope that one of these checks might expose and help remedy the situation. Indeed, we would hope that a teacher would recognise this for themselves and be supported with professional development. This opens up other measures of the quality of our teacher education – if it produces reflective practitioners dedicated to lifelong learning and improving their own practice.

In summary, we hope to have presented a few reasons why the numeracy skills of new teachers should not be considered a crisis. We already assess teachers’ numeracy skills in much more meaningful ways than a quick and dirty test, and we have wide-ranging quality control processes throughout teacher education and the profession as a whole. What we want to argue instead is that we need to think more about all the different information we have, or might like, about the quality of teacher education and how we can use that to guide improvements.

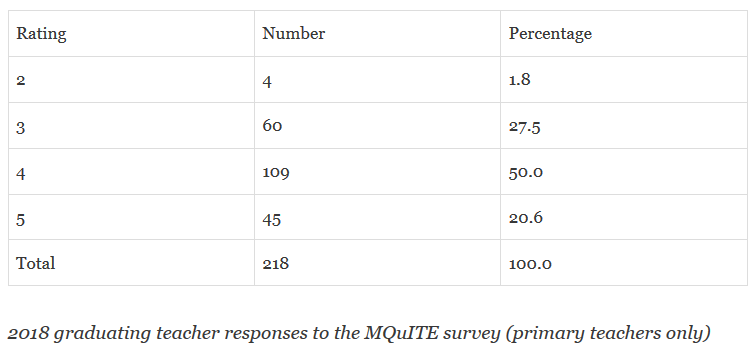

Obviously, we think the Measuring Quality in Initial Teacher Education (MQuITE) project is vital for this effort, but we also want to point out the value of taking a more nuanced view in general and not over-rely on any one source of data or anecdote. For example, here’s some data from our 2018 survey of graduating teachers which reveals a different picture of ITE graduates’ numeracy preparedness than did the Parliamentary Inquiry. From a sample of 332 graduating students (about 10% of the population) and with good representation across the range of universities and ITE routes, we can start to look at the question “Are teachers ready to teach numeracy?” As the article that prompted our blog discussed 11-year olds, we’ll look at primary teachers. On a 5-point scale, we asked how prepared students felt to enter the teaching profession and then how prepared they were to teach different curricular areas. Anything above 3.0 is a positive rating, where 5.0 would mean that every teacher felt completely prepared and 1.0 that every teacher felt completely unprepared. Overall preparedness was rated at a mean of 3.74, matching the average preparedness rating (3.73) of all the individual curricular areas – so overall positive. When we just look at the maths and numeracy question, we see the mean is actually higher, at 3.89. When we look into these responses even more (see the table below of 2018 graduating primary teachers), we find that no students reported feeling completely unprepared for teaching numeracy and maths, and that only 1.8% of our sample gave a negative rating.

So, when we look at the data from a much larger sample, we see that not only are teachers feeling broadly prepared for teaching maths and numeracy, they actually feel more prepared in this subject than they do across the curriculum in general.

Clearly we are using self-reported data here (although so was the education committee), but the sample is good, the survey is reliable, and responses were anonymous. Other data sources also reflect improvements in numeracy. For instance, The Scottish Survey of Literacy and Numeracy also suggests that teachers gain in confidence, with 99% of surveyed teachers over the last 5-years rating themselves as confident or very confident in 5 of 8 areas of numeracy. In terms of pupil outcomes, we might also look at Attainment and Leavers’ Destinations data which shows 96.3% of students leaving school with level 3 or higher numeracy (up around 10 percentage points since 2012/3).

As MQuITE develops, more data will be shared. For now, however, we might just want to take some encouragement from what the 2018 graduating teachers are telling us.

MQuITE blog posts are co-authored. This post by Dr Mark Carver (@themarkcarver), Dr Paul Adams (@pauladams40), and Dr Aileen Kennedy (@DrAileenK). Project update tweets are @MQuITE_Ed.